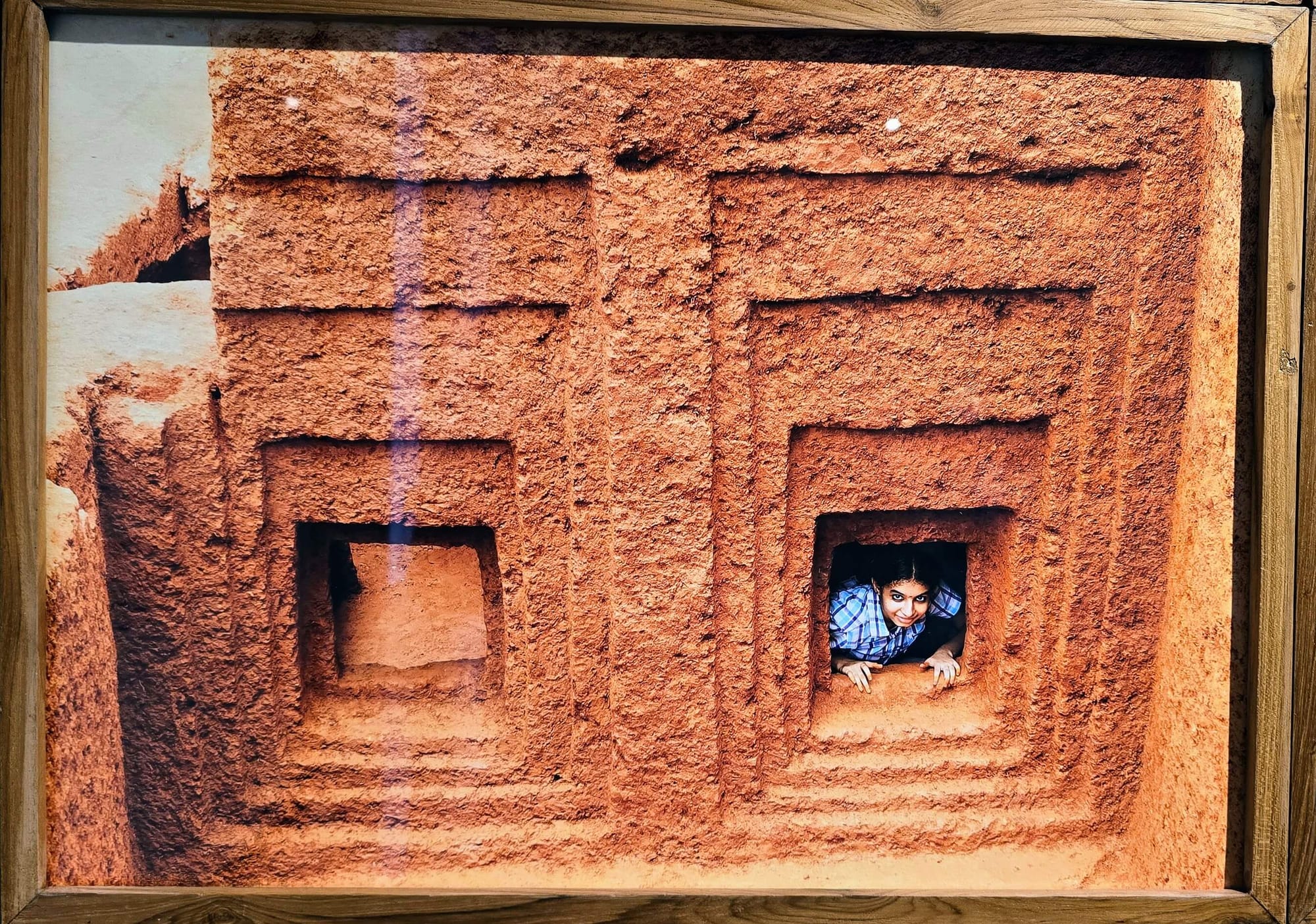

When does a photograph stop being documentation and become an artefact itself Can pre-historic artifacts be art? This Fort Kochi Exhibition at Kara by Mohamed A exhibition says yes!

Visiting Information

Venue: Kara (next to Lila, near Parade Ground, Fort Kochi). Free Entry

Beyond the scalloped walls of Kara lies a serene space that combines old world charm with contemporary luxury. Part Dutch, part art deco, part modern minimalism.

Kara Hotel, Fort Kochi, Kochi, Kerala

Walk into the beautiful Kara gallery and this question will stop you mid-step. Mohamed A, a photographer with over two decades of experience documenting Kerala's buried histories, invites you to travel through time—not through words, but through his lens trained on sites where ancient hands left their mark on stone, earth, and bone.

The Photographer as Archaeologist

In archaeology, photographs are usually afterthoughts—technical aids, figure numbers in reports, illustrations for journal articles. The photographer remains invisible, a "spectral non-presence" as Mohamed A describes it. But what happens when we flip this relationship? What does the photographer actually see at an archaeological site? What stories emerge when the camera becomes a tool of discovery rather than mere documentation?

This is the central inquiry of "Archaeological Camera"—a visual journey through Kerala's prehistoric landscape that spans the Neolithic to the Iron Age, from 4,000 BCE to roughly 400 CE.

Sites That Speak

The exhibition covers eight archaeological locations across Kerala, each with its own buried narrative:

Ettukudukka in Kannur's midland region, where geoglyphs carved into exposed laterite depict herds of eastward-moving cattle with prominent humps. These rock carvings share visual language with similar finds across the Konkan Coast, suggesting ancient communities that communicated through stone across vast distances.

Marayoor in Idukki's Western Ghats shelters some of Kerala's most significant rock art. Several shelters preserve pictographs in red ochre and white kaolin—animal figures, human forms, honeycomb patterns, and what appears to be a sambar deer with calf. The superimposed and varied styles suggest the sites were used across multiple periods, a palimpsest of early cultural expression.

Anakkara in Palakkad preserves Iron Age monuments raised by iron-using communities. Dressed stone blocks arranged in circles and umbrella-like formations still stand on laterite hillocks. The caves carved into the laterite bed once held large ceramic urns containing fragmented bones, grave goods like pots and iron implements—all methodically packed by hands that lived over two millennia ago.

Kakkodi in Kozhikode emerged by accident—during shrub clearance for house construction in 2014, workers stumbled upon a megalithic rock-cut cave on a hillock called Chirattumala. The Kerala Archaeology Department's excavation yielded burial goods including a rare iron hanger and semi-precious beads of etched carnelian and agate. AMS dating placed these remains at approximately 2,600 years before present.

Cheemeni in Kannur district tells a sadder story—rock-cut caves at Pothamkandam were excavated by the Kerala State Department of Archaeology, but local disturbance had already compromised the site. Only broken potteries and a small number of iron objects were recovered.

Parambathukavu in Malappuram has revealed an extraordinary range of cultural remains—microlithic tools, petroglyphs, terracotta figurines, a megalithic rock-cut cave, postholes, and even a Devi temple within a sacred grove (kavu). The postholes, occurring in rows, circles, or ovals with broad grooves, may represent temporary huts or platforms used in funerary practices.

Kaliyathumukku in Kozhikode's Arikulam village surprised everyone during house construction when workers discovered a rock-cut cave with two long rectangular chambers. The excavation yielded around thirty-four potteries, but notably lacked iron implements—a curious absence that distinguishes this site from similar caves elsewhere.

About Mohamed A

Mohamed A hails from Thiruvananthapuram and has dedicated over twenty years to photography. His work earned him the Junior Fellowship for Photography from the Ministry of Culture, Government of India (2002-2004). His portfolio captures nature alongside the diverse lifestyles, cultures, and traditions of various communities across India.

His expertise in documenting archival and archaeological materials has broadened his creative practice significantly. He has contributed museum catalogues and handbooks for the Muziris Heritage Project, excavation reports for the Kerala State Archaeology Department, and photobooks documenting sites like Edakkal Cave in Wayanad.

In 2018, Mohamed A made his cinematography debut with the Malayalam feature film Udalazham, directed by Unikrishnan Awala, which screened at national and international film festivals. He has since worked on five additional feature films, continuously exploring the nuances of visual storytelling.

Why This Exhibition Matters

Kerala's rock art and megalithic sites remain largely unknown even to many Keralites. Unlike the famous Bhimbetka caves in Madhya Pradesh, our prehistoric treasures—the rock paintings of Marayoor, the petroglyphs of Edakkal and Ettukudukka, the megalithic burial sites scattered across the Western Ghats—don't feature prominently in school textbooks or tourism brochures.

"Archaeological Camera" bridges this gap by making these distant sites present in Fort Kochi. Through Mohamed A's lens, we're invited to consider what's absent from the frame—the shadows, tools, footprints—and what led up to each moment captured.

More about Kerala's heritage: Read our coverage of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2025 schedule and discover Mattancherry Palace's royal history.

![Mattancherry Food Walk: A Culinary Journey in Fort Kochi [Feb 13]](/content/images/size/w30/2026/02/eating-and-drinking-partition-svgrepo-com.svg)

![Short Stories, Long Shadows: Contemporary Malayalam Voices at Fort Kochi [Feb 4-6]](/content/images/size/w30/2026/02/writing-svgrepo-com.svg)

![Tales From The Table: Peruvian & Mattancherry Food Traditions Meet in Fort Kochi [Feb 4]](/content/images/size/w30/2026/02/cooking-pot-svgrepo-com.svg)

![Math Meets Art at Kochi Biennale [Feb 3,4]](/content/images/size/w30/2026/02/geometry-dash-svgrepo-com.svg)