Imagine its 1947, a woman on a bicycle is riding through Delhi with a nine-kilogram camera strapped to her back. She photographed the first flag hoisting at the Red Fort, Mountbatten's last salute, and Gandhi's funeral.

Her name was Homai Vyarawalla, and most people have never heard of her. Now, inside a colonial jail in Fort Kochi where freedom fighters were once locked up, her photographs are on display. The irony is hard to miss.

Walk past the Fort Kochi police station and you'll find a small compound most visitors overlook. This is the Jail of Freedom Struggle - a colonial-era prison where Indian freedom fighters like Mohammed Abdul Rahman, AK Gopalan, and EMS Namboodiripad were locked up by the British. Eight cramped cells, each just 50 square feet, with concrete beds and cast iron doors.

Today, this jail is one of the most powerful exhibition spaces at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2025-26. And what's inside is just as powerful as the walls.

What's the Exhibition?

Re: Public/Staging: Delhi is presented by the Alkazi Theatre Archives in collaboration with the Alkazi Collection of Photography. It's part of the Biennale's Invitations programme - a platform that shares space with nonprofit and artist-led initiatives from across the world.

The exhibition has two parts that talk to each other in surprising ways.

Part One: Homai Vyarawalla and the Republic

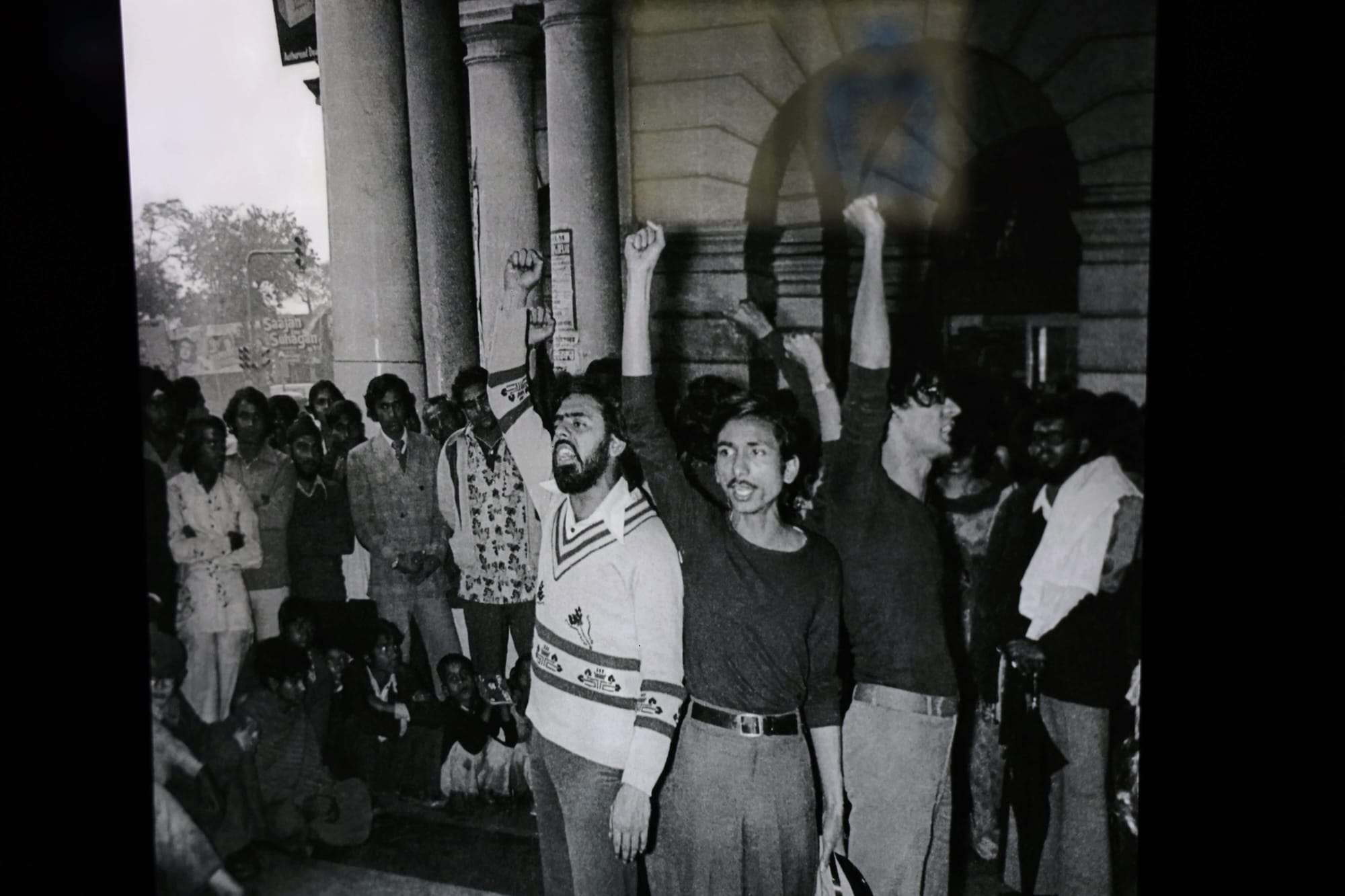

The first part, Re: Public (2024), shows photographs by Homai Vyarawalla - widely recognised as India's first woman photojournalist.

Here's the short version of her story. Born in 1913 to a Parsi family, Homai learned photography from her boyfriend (and later husband) Manekshaw Vyarawalla while studying at the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay. In the 1930s, when there were almost no women in the press, she started publishing photo-features in The Illustrated Weekly of India and The Bombay Chronicle. Because she was a woman, her early photographs were published under her husband's name.

In 1942, she moved to Delhi and joined the British Information Service. Picture this: a woman in a sari, cycling through the capital with a heavy camera, showing up at political events where every other photographer was male. People didn't take her seriously at first. That was her advantage - she could get close, stay unnoticed, and take photographs no one else could.

She became one of the most important visual chroniclers of post-Independence India. She photographed Nehru (her favourite subject), Gandhi, Jacqueline Kennedy, Queen Elizabeth II, the Dalai Lama, Ho Chi Minh, and Clement Attlee. She captured both the joy of Independence and the pain of Partition. She retired in 1970, disillusioned with the rise of paparazzi-style press. In 2011, she received the Padma Vibhushan - India's second highest civilian award. She died in 2012 at 98.

The photographs on display here focus on something specific: Rajpath (now Kartavya Path) and the Republic Day parades of 1950 and 1951 - the very first ones after India became a republic. There are also staged images of diverse cultural groups, modern technology, and medicine - all reflecting the Nehruvian dream of a modern, plural India.

Think of it this way: India had just become a republic. The parade was the new nation performing itself for the first time. And Homai was there to record it.

Part Two: Delhi's Forgotten Theatre Spaces

The second part, Re: Staging 1990s (Delhi) (2025), goes in a completely different direction - but somehow it connects.

This section pulls together materials from the book Delhi Modern: The Architectural Photographs of Madan Mahatta, along with theatre brochures from plays performed in Delhi in the 1990s and theatre texts from that decade.

The exhibition maps out Delhi's theatre venues - buildings that were never built as theatres but became them. Colonial government buildings were repurposed. Open-air amphitheatres were carved out of lawns. The fan-shaped proscenium, the intimate black box - all these forms were experiments in a young nation figuring out what its public cultural life should look like.

Some of the venues mapped in the exhibition include the Kamani Auditorium (started 1971, Copernicus Marg), the Little Theatre Group auditorium (founded in Lahore in 1946, migrated to Delhi in 1947), the Meghdoot Open Air Theatre at Rabindra Bhavan (a mud-and-brick stage built by E. Alkazi himself in 1967), Studio One at Rabindra Bhawan (an 80-seater mini auditorium carved from two rooms by Alkazi in 1964), and the National School of Drama housed in Bahawalpur House - the former residence of the Nawab of Bahawalpur.

There's a beautiful detail here. Rabindra Bhawan was built in 1961 to mark the birth centenary of Rabindranath Tagore, on the direction of Nehru himself. It houses three National Academies: Lalit Kala (visual arts), Sangeet Natak (performing arts), and Sahitya (literature). The architect was Habib Rahman.

The 1990s angle is important too. That decade brought major economic and political changes to India - liberalisation, the Babri Masjid demolition, new cultural politics. The exhibition asks: how did theatre respond? How did stage work become a form of cultural action?

Why you should not miss this

Here's what makes this exhibition special at the Biennale. It's not just about what's on the walls - it's about where you're standing.

You're looking at photographs of India performing its new nationhood (the Republic Day parades) and the buildings where India rehearsed its cultural identity (Delhi's theatres) - and you're doing this inside a jail where people fought and suffered for that very freedom.

The venue is the exhibition's silent third act.

The Alkazi Connection

Both parts of this exhibition come from the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, a privately owned collection in New Delhi started by Ebrahim Alkazi - one of the most influential figures in Indian theatre. The Foundation houses the Alkazi Collection of Photography (over one lakh 19th and early 20th century photographs) and the Alkazi Theatre Archives (scripts, director's notes, brochures, reviews, and audio-visual material from post-Independence Indian theatre).

The Theatre Archives were initiated in 2016 and approach theatre not just as performance but as a social document - evidence of how a society thinks, argues, and imagines itself.

Visiting Details

Exhibition: Re: Public/Staging: Delhi Presented by: Alkazi Theatre Archives in collaboration with Alkazi Collection of Photography Venue Link: Jail of Freedom Struggle, Fort Kochi Programme: Invitations, Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2025-26 Dates: December 12, 2025 - March 31, 2026

The Jail of Freedom Struggle is near the Fort Kochi police station, a short walk from the main Biennale venues. If you're coming from Aspinwall House, it's easy to include this on your route.

For more on what to see this season, check out our guide to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2025-26 and the full 32 things to do in Fort Kochi.

![Taala Tamate at Kochi Biennale: A Drum That Was Silenced Now Takes Centre Stage [Feb 15]](/content/images/size/w30/2026/02/drum-svgrepo-com.svg)

![Indus Valley Dancing Girl: Hallucinations of an Artifact [Feb 14,15]](/content/images/size/w30/2026/02/rhythmic-gymnastics-svgrepo-com.svg)